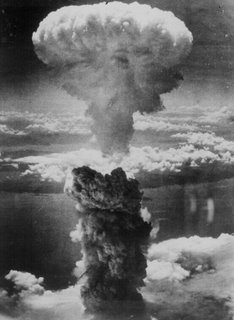

Hours after this attack, the Washington Press Club prepared the first “Atomic Cocktail,” made from a combination of gin and Pernod--a bright green, anise-based liquor. When mixed with another liquid, Pernod immediately develops a cloudy white hue. This stunning transformation allowed Americans everywhere to simulate an atomic explosion from the comfort of their own kitchen! With the advent of the “Atomic Cocktail,” each home in America was now equipped to participate in the Atomic revolution.

In the days to follow, “Atomic” became a buzzword in America. Two days after the U.S. dropped the first bomb, Life magazine featured a full-page photograph of a starlet clad in a two-piece bathing suit, naming her “Miss Anatomic Bomb.” Shortly thereafter, Los Angeles burlesque houses began to feature “Atombomb Dancers.” And in December of 1945, country western singers Karl Davis and Harty Taylor recorded a song entitled “When the Atom Bomb Fell”--the first musical response to the deadly nuclear blasts.

In the days to follow, “Atomic” became a buzzword in America. Two days after the U.S. dropped the first bomb, Life magazine featured a full-page photograph of a starlet clad in a two-piece bathing suit, naming her “Miss Anatomic Bomb.” Shortly thereafter, Los Angeles burlesque houses began to feature “Atombomb Dancers.” And in December of 1945, country western singers Karl Davis and Harty Taylor recorded a song entitled “When the Atom Bomb Fell”--the first musical response to the deadly nuclear blasts.

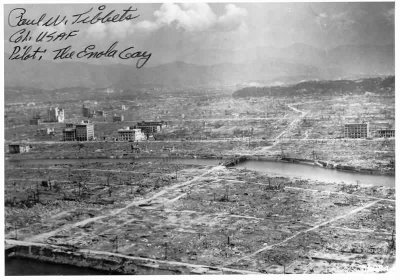

Although the initial reactions to the Atom bomb were lighthearted, as the American public learned more about the bomb’s potential for mass destruction, anxiety blossomed. In March of 1946 the Federation of Atomic Scientists published a small paperback volume entitled One World or None, which described a hypothetical nuclear attack on the United States. This book quickly became a national bestseller. Similarly, in August of 1946, John Hersey’s account of Hiroshima in the wake of nuclear attack was published in The New Yorker. This article was subsequently published in book form and also became a national bestseller.

Reports of radioactive “fall-out”--a product of nuclear testing--heightened levels of anxiety. (The word “fall-out” first appeared in the New York Times on August 17, 1952: "Nevertheless, a good deal of radioactive stuff is picked up and carried by the wind and deposited all over the country... So far there have been no dangerous concentrations of radioactive ‘fall-out,’ as it is called, that is outside of the proving grounds in Nevada.")

President Eisenhower encouraged the Atomic Energy Commission to capitalize on the public’s lack of knowledge regarding the specifics of nuclear science. AEC Chairman Gordon Dean reported that Eisenhower said, “Keep them confused as to ‘fission’ and ‘fusion’.”

Eisenhower, who wanted to proceed with nuclear testing, viewed American anxiety as a threat to the development of a nuclear artillery. That said, he was aware of the rhetorical power of words like “fall-out.” By limiting the public’s exposure to such words, Ike hoped to keep Americans ignorant--eliminating fear and subsequent resistance to nuclear testing.

Unfortunately, Ike was too late. By the mid-Fifties, the atomic lexicon had become an integral part of American life. Elimination (or even suppression) of this lexicon was no longer possible and anxiety continued to swell throughout the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Today, 61 years after the first nuclear attack, we seem to be tormented by a similar set of set of anxieties. Although we no longer hear talk of "hydrogen bombs" and "fall-out shelters," the news is littered with comparable doomsday buzzwords. Not a day goes by without discussion of "uranium enrichment," "weapons of mass destruction," or "long range missiles."